Ethical research with vulnerable communities

March 11, 2024

Ethical practice has a lot to do with the specific groups or communities involved in a research project. […] Research participants from diverse backgrounds may have different expectations when it comes to privacy, data governance, and knowledge sharing.

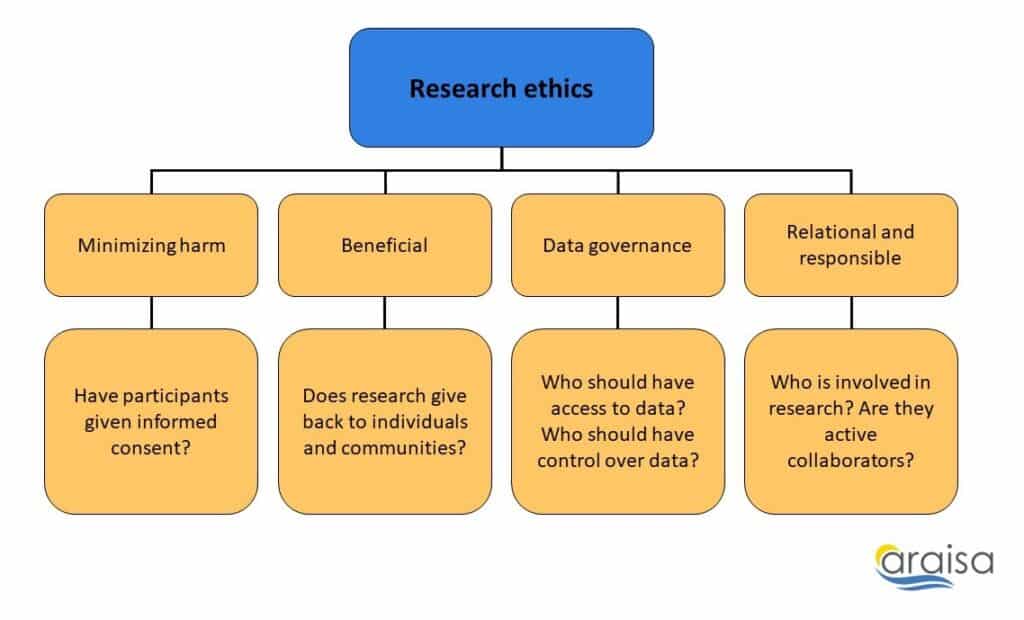

Research should always be conducted in an ethical manner. But how do researchers select an ethical framework and adhere to its principles? For those working in a university or large institution, ethical practice is usually governed by a research ethics board (REB). In this context, research ethics usually means minimizing harm while ensuring participants are fully informed about possible risks. In a smaller, community-oriented setting, ethical practice may involve giving back to communities, which requires healthy relationships between researchers and research participants. A researcher might therefore ask: What is my relationship to the community being studied? Have I established a respectful relationship with them? How will this research directly benefit the participants and the communities they belong to?

Ethical practice has a lot to do with the specific groups or communities involved in a research project. While REBs require researchers to adhere to a strict set of guidelines – often based on confidentiality and consent – these principles may not apply to every community in the same way. Research participants from diverse backgrounds may have different expectations when it comes to privacy, data governance, and knowledge sharing. This is especially important to consider when working with people from vulnerable communities, such as the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, people living with disabilities, or racialized newcomers. It is crucial that researchers work to understand a community’s expectations for ethical data collection and use.

The FAIR and CARE principles highlight the often shifting nature of ethical research practice. The FAIR principles assert that ethical research involves making data open and freely accessible. When applying these principles, researchers will produce data that is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable to a wide range of researchers and other data users. But while it is important for certain datasets to be widely available, there has also been pushback to this idea, especially when research involves Indigenous peoples. For example, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance developed the CARE principles partly in response to FAIR. The CARE principles maintain that when research involves Indigenous communities, these communities should retain ownership and control of data. In particular, research should have collective benefit for the communities involved; Indigenous communities must have authority to control data; researchers have a responsibility to demonstrate how data benefits communities; and ethics should ultimately place Indigenous rights and well-being at the core of data use.

Researchers should work closely with participants to identify how research can give back to individuals and communities.

Contrasting these approaches to data management highlights key aspects of ethical research practice, especially when it involves vulnerable communities. First, research is a collaborative process. It can involve a researcher or team of researchers, one or more communities, and a range of partners or collaborators. Every party is responsible for the ethical collection and use of data. Second, communities should remain involved at each stage of the research process. This may involve giving communities the right to control data, although it may also involve making data more widely available. Finally, research should benefit the people involved. Researchers should work closely with participants to identify how research can give back to individuals and communities.

Ethical research practice is important in the settlement sector because newcomers often belong to vulnerable communities. I am not aware of any widely used ethical principles designed specifically for research with newcomers, although a few organizations have developed useful guidelines. The International Association for the Study of Forced Migration has developed a code of ethics related to people experiencing forced migration. The Hamilton Immigration Partnership Council has a useful guide for doing research with newcomers, which stresses the value of meaningful and inclusive research. The National Newcomer Navigation Network also provides a set of resources for doing ethical research involving newcomers.

Jason Chalmers, PhD

Research Lead / Responsable de la recherche

About the Author

Jason Chalmers

Jason Chalmers holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Alberta and was a Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Community and Public Affairs at Concordia University. As an interdisciplinary researcher, Jason draws on diverse methodologies and is particularly inspired by creative and community-based practice. Jason’s research interests include Canada’s immigration history, Indigenous-settler relations, and social inequality.

You can reach Jason at jchalmers@araisa.ca